The Best Movies of the 21st Century (No 24): AMOUR

I again opt for a foreign film for an honoured place on my Top 25 list. In the Mood for Love was Chinese and Amour is a French production. People are going to begin to think I am anti-American. Worry not- some great American movies will appear as we move up the list. For now, I recognise the cinematic brilliance of Amour, a 2012 film directed by Michael Haneke. Amour is a great movie- a profound and challenging examination of love, mortality and human dignity. It is a multidimensional masterpiece- an intimate love story that is an unflinching study of aging, illness and decline. It is brutal and unsettling, unnerving in its honesty and unsparing in its depiction of death and dying. It is refreshingly unsentimental in its approach to issues that typically invite melodrama. Mr Haneke succeeds although the emotional demands the film makes on the audience are extreme and not all moviegoers will possess the fortitude to stick with the movie to the bitter end. On a personal level I admired the decision to tackle difficult themes in such a powerful way.

The film follows Anne and George Laurent, retired piano teachers in their 80’s. They have a comfortable Paris apartment and their life in retirement has a civilised rhythm. They are aging gracefully. Unfortunately, their blissful life is shattered when Anne suffers a stroke during breakfast. What begins as a temporary episode becomes a devastating and relentless journey of physical and cognitive decline. Their marriage is transformed from one of endearing companionship to an exhausting caregiving relationship. George, honouring his promise never to send Anne to a nursing home becomes her sole caretaker as she loses the ability to speak, move or recognise the world around her. Tough stuff!

Haneke’s direction was masterful and he won the Palme d’Or at the 2012 Cannes film Festival. The film’s critical reception was equally extraordinary, earning 5 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director. It won the Oscar for Best Foreign film. Metacritic, reflecting the views of major international for critics gave it a score of 95/100- an off the charts consensus on the artistic excellence of the production. I am not bucking the crowd here with my appreciation of the film.

The challenges presented by Anne’s decline are rendered with clinical detail. We witness George bathing his wife, feeding her, exercising her paralysed limbs and adjusting to her loss of speech and comprehension. George’s profound love confronts feelings of frustration and helplessness. He is tender, but exhausted. In one devastating scene his patience cracks when he slaps Anne when she spits out the water he is trying to give her. We also witness complex family dynamics. They have a daughter Eva, played by Isabelle Huppert. She is a talented musician and tours Europe for concerts regularly. She is impressive, but the relationship with her parents is strange. Their interactions are formal, almost businesslike and she vigorously opposes George’s decision to assume the caregiver role. She doesn’t understand the depth of her parent’s bond or George’s commitment to honouring Anne’s wishes. She doesn’t add much value and quickly returns to her more glamorous life in the great concert halls of Europe. The isolation of George and Anne is a theme here. Friends and family are not comfortable with the long slow goodbyes of ailing octogenarians. A visit from her prized student Alexander starts off with promise, but ends poorly. Music has been the foundation of the couples married life and Anne has lost the ability to engage in that arena as well. The grand piano in their living room goes silent- it s just a prop- a piece of furniture in a depressing household.

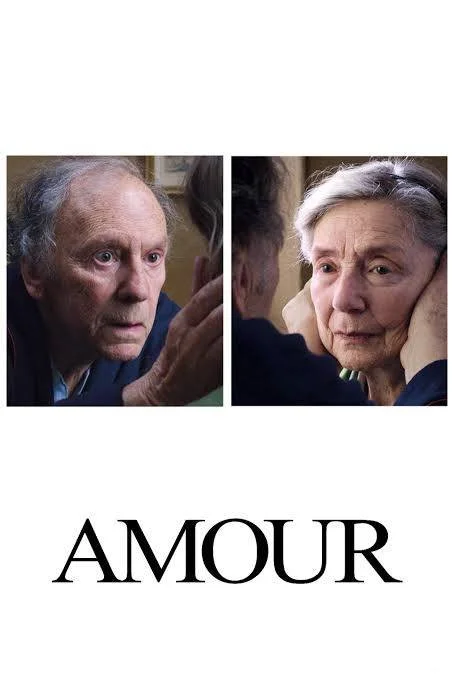

Jean Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva deliver towering performances. Trintignant, of A Man and a Woman 1960’s fame came out of retirement for this role. He brings remarkable depth to George’s journey from devoted husband to angel of mercy. Riva creates a character whose dignity persists even as her faculties disappear. You like and respect her and her gradual loss of faculties is devastating. Haneke’s direction is polished and warm. The apartment becomes a character - a space filled with books, music and memories that slowly transforms into a medical facility and finally a tomb. Amour forces the audience to confront difficult questions. What do we owe our loved one’s when they are suffering? When does loyalty become imprisonment? Haneke provides no easy answers, but he captures the moral complexities. The movie is unflinchingly honest. Its authenticity jumps off the screen and makes it essential cinema. Well done Frenchies!!